Age-related neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia have high prevalence in those over 65 years of age [1,2]. These diseases are characterized by neuron damage and death, leading to cognitive decline, predominantly in memory, language, and thinking. As a progressive disease, symptoms worsen over time, and patients may present with personality changes and, eventually, inability to perform daily tasks. Currently there is no way to prevent or cure AD or dementia, though identifying genetic risk factors may delay the onset of symptoms.

Much of the field currently focuses on understanding the underlying biology of Alzheimer’s and dementia to slow disease progression and to identify new therapy targets to alleviate symptoms. A recent study by Greda et al. identifies a lipoprotein receptor sortilin which may link dysfunctional neuronal lipid metabolism with these neurodegenerative diseases [3].

Sortilin’s Delivery Service

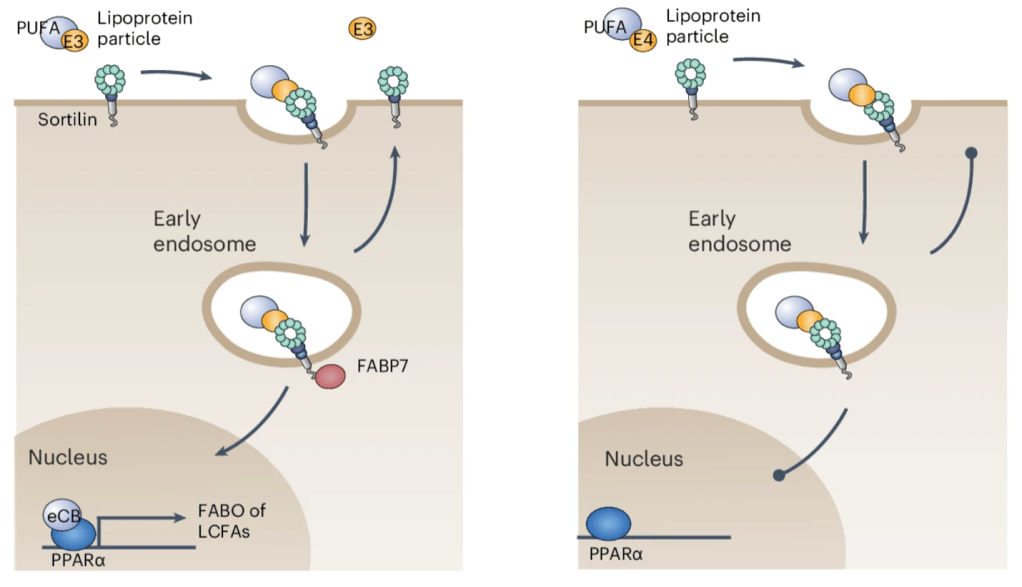

Genome-association wide association studies (GWAS) are often used to identify a certain gene mutation that appears repeatedly within a population. SORT1, the gene that codes for the protein sortilin, has been previously identified as a hit in several of these studies for Alzheimer’s, and frontotemporal lobe dementia. The authors previously reported that sortilin is expressed in the brain’s nerve cells where it acts as a receptor for lipoproteins, which are molecules that are responsible for transporting lipids [3]. One such lipoprotein is apolipoprotein E (apoE). Several forms of apoE exist, most notably apoE3. The authors propose that when sortilin “sees” apoE3, it engulfs it and its accompanying/bound lipid, and where it is taken up by neurons for fuel (metabolism). Once the lipid is released, the sortilin and apoE3 return to the cell surface, termed “receptor recycling”. However, when apoE3 is replaced with a different form, apoE4, this recycling and lipid metabolism is disrupted.

The involvement of apoE4 in this process is particularly interesting as individuals expressing this form of the gene have the highest risk of developing Alzheimer’s [4]. Greda et al. go on to show that without sortilin, mouse and human neurons are unable to consume long-chain fatty acids, which lead to decreased neuron function, signaling, and survival. Interesting, even if neurons have sortilin, their health is still impaired if they are receiving apoE4 instead of the most common apolipoprotein form, apoE3.

PPAR-t of the solution?

To identify the mechanisms behind this phenomenon, the authors used stem-cell derived neurons to find gene-level changes in sortilin-deficient and healthy neurons. Several experiments converge to reveal the deactivation of PPARα-dependent genes, a pathway involved specifically in lipid metabolism and inflammation. When researchers stimulate this pathway, they can rescue the deficiencies of sortilin-deficiency and promote the uptake and consumption of long-chain fatty acids again. Ultimately, these findings show the importance of long-chain fatty acids in neuronal health, even in normal glucose conditions. This fuel source becomes even more important in cases where glucose levels are depleted, such as stroke, aging, and neurodegenerative disease. While many pathological mechanisms have been reported for apoE4, the most common genetic risk factor of Alzheimer’s, this new link between apoE4 and neuronal lipid metabolism cites a new direction for therapy development.

Written by: Caitlyn Dang

References:

- PMC12040760

- PMC3932112

- PMC41102453

- PMC7104324

Leave a comment