The intestine has the remarkable ability to grow and change under the pressure of demanding conditions. Previous work examining intestinal plasticity has shown the response to nutrient excess/depletion, changes in the microbiome, and tissue damage. However, one large causal factor has been historically overlooked–pregnancy.

The lining of the intestine has dynamic crypts and villi that are constantly self-renewing. At the crypt base, stem cells divide and differentiate into secretory cells, which secrete mucus, or enterocytes, which absorb nutrients. These cells move up along the villi and undergo cell death at the tip, creating a renewal process of about 3-5 days.

In Cell, Tomotsune Ameki et al. show that reproduction causes intestinal elongation and rapid crypt renewal, a process that is anticipatory and genetically controlled.

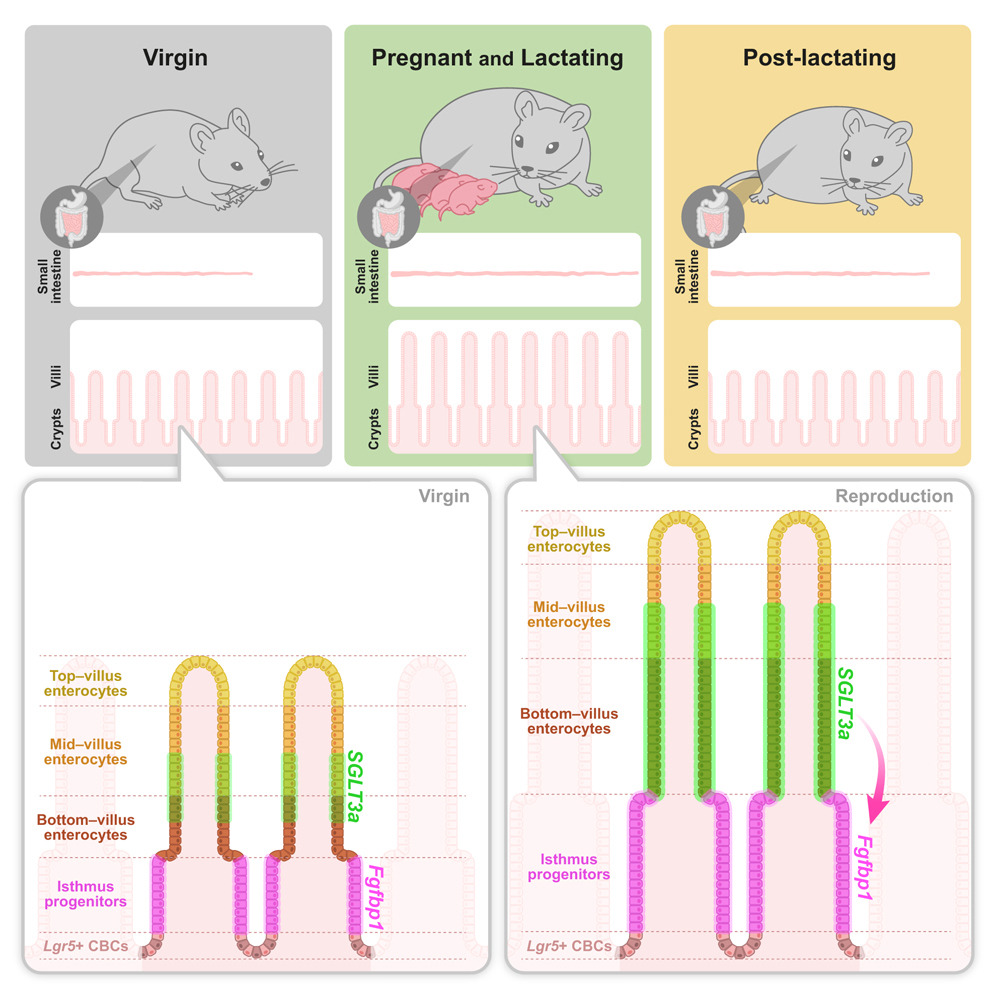

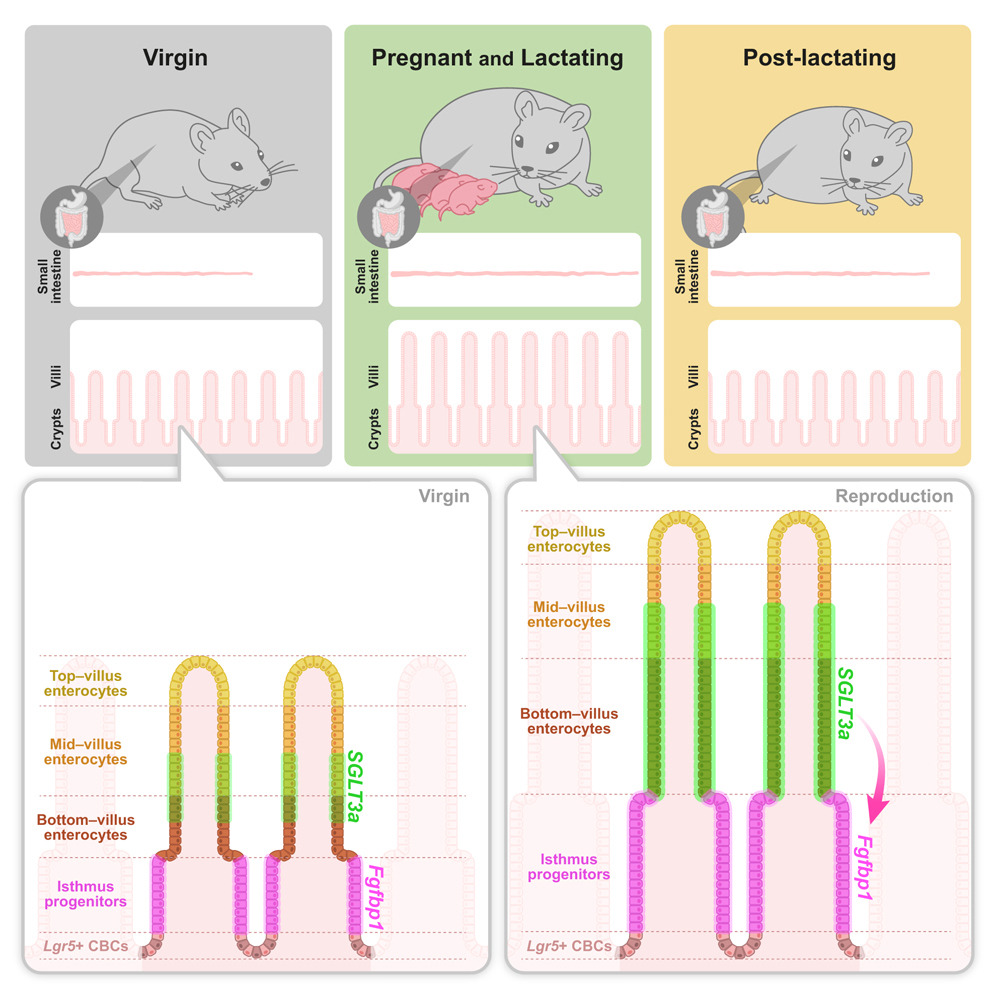

The authors first wanted to characterize how reproduction alters intestinal plasticity. Using female mice, they measured intestinal length and crypt dynamics at four timepoints: postnatal day 7 (P7), postnatal day 18 before birth (P18), lactation day 7 (L7), and 35 days postlactation (PL35). They discovered that at the end of pregnancy, the small intestine was 18% longer compared to virgin females. With a second pregnancy, the intestine further lengthens, showing that elongation is cumulative with multiple pregnancies. Whether there is a limit to how long the intestine lengthens with each pregnancy was not explored, but it would have interesting implications for mothers with more than two children. Could this contribute to more difficult weight loss after a second baby?2 Reproduction also affected the intestinal epithelium through deepening crypts and increasing villi width by the end of the pregnancy. Unlike intestinal elongation, epithelial expansion was fully reversible postlactation.

Growth in crypt depth and villus height may ensue from changes in cell size or cell number. To understand the root cause, the authors traced progenitor cells and examined their proliferation and the speed at which they moved along the villus. At L7, not only did proliferation significantly increase, but villus renewal only took 24 hours–compared to 3-5 days in virgin females.

To identify what molecular changes could drive reproductive remodeling, the authors performed single-cell RNA sequencing in virgin, pregnant, and lactating female mice. The data showed an increase in expression of the gene Slc5a4a, which encodes for SGLT3a, a sodium-glucose cotransporter, in pregnant and lactating females. Staining for Slc5a4a showed it was upregulated in bottom and mid-villus enterocytes and was adjacent to progenitor cells. Enterocytes differ in nutrient absorption depending on their location on the villus, suggesting SGLT3a could play a role in nutrient absorption in the maternal intestine and possibly affect milk composition.

The authors then utilized virgin and lactating SGLT3 knockout mice to determine if it is responsible for remodeling. Compared to control females, SGLT3 knockout females had 45% less villus growth in addition to reduced proliferation and villus renewal during lactation.

Tomotsune Ameki et al. demonstrate that reproduction causes intensive intestinal remodeling. Moreover, the intestine begins to change before maternal food intake increases during pregnancy, suggesting such changes are anticipatory. Exploration into the hormonal role in maternal intestinal plasticity could elucidate how Slc5a4a is upregulated and the genetic mechanism of remodeling.

Overall, the authors resolve a huge black box in reproductive health, and our new understanding of reproductive intestinal plasticity may be used to improve maternal and infant health outcomes.

Written by: Michelle Seeler

References:

[1] PMID: 40112802

[2] Aggarwal, Nehal. (2024). Postpartum Weight Loss: Tips for Losing Weight After Baby. The Bump.

Leave a reply to David S Cancel reply